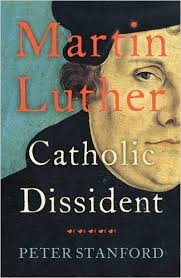

Martin Luther: Catholic Dissident by Peter Stanford.

Peter Stanford’s name will not be unfamiliar to readers of the Telegraph or the Guardian/Observer, as both titles publish his work. He seems to specialise in writing on religion, particularly Catholicism; writing obituaries, particularly those of Catholic prelates; and writing about prisons, particularly in terms of the Longford Trust and penal reform.

Stanford lives in North Norfolk and attends mass at his local Roman Catholic church. Communion is administered by an ex-Anglican married priest. The celebrant preferred to convert to papacy rather than work alongside women priests and bishops in the Church of England. Stanford’s biography concerns another man of principle, although it was papal abuses against which Luther stood firm.

The introduction plays on the legend that Luther’s career in the church began when he was terrified, having been caught out in the open by a violent and cacophonous thunderstorm. He was so frightened that he promised Saint Anne, the Holy Virgin’s mother, he would become a monk.

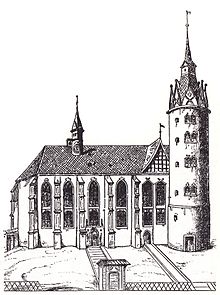

Whilst dismissing the credulity of the tale, Stanford creates, for himself, an elaborate conceit: he is in Wittenberg, soaked to the skin by a storm, sheltering in a doorway, sequestering a Playmobil model of Martin Luther in his drenched pocket. He is then welcomed – even though a Catholic – into Luther’s own church, the Stadtkirche, by the Lutheran Rev. Cliff Winter from Wichita, Kansas. You couldn’t make it up. Or could you?

Whatever the accuracy or exaggeration of the story, it’s a good one and a warm reception to a text which looks like it might be quite challenging. Lucas Cranach’s 1529 portrait of Martin Luther, which graces the cover, shows a serious face with thin determined lips. We know that Luther’s life will be a series of acts of courage resulting in privation and excommunication. There won’t be many jokes along the way. Well, have you heard the one about the Diet of Worms?

Luther’s ideas contributed to a century of religious wars followed by centuries of internecine conflict, culminating in 1999 with the ‘Joint Declaration on the Doctrine of Justification during the Catholic-Lutheran talks at the Vatican. Justification by faith was the central issue for Luther: faith, or love of and belief in Christ, was the only way to salvation. The ‘95 Theses’ is a list of short debating points on the subject of indulgences.

Luther was disgusted by the contemporary habit of buying indulgences. These, sold by the church, could be used to ensure one’s own, or a loved one’s, place in heaven. But Luther believed that indulgences had no power and were corrupt. When Luther’s ‘95 Theses’ arrived in Rome the Vatican was using the money raised to build St. Peter’s. Luther suggests that Leo X, who was as rich as Croesus, should pay for the cathedral himself. That is the content of thesis 86.

Luther also took exception to four of the seven sacraments. He approved of the Eucharist, of child baptism and of confession. These three he thought were the only ones coming directly from Christ. Also they bring the believer closer to God. Additionally they cannot be manipulated by powerful priests. Confirmation, marriage, holy orders and extreme unction did not make the cut. As can be seen these excisions would have reduced the role and power of the Catholic clergy.

Leo X dismissed Luther’s ideas and refused to enter into discussion or debate. Demands were made that Luther recant and when he did not he was excommunicated in 1521. Frustrated and disappointed, Luther and a growing band of dissenters broke free of Roman Catholicism and set up the Lutheran Church.

What is there to celebrate in 2017? According to Stanford, Europeans owe Luther a ‘debt’ because he broke ‘the stranglehold of the late medieval Catholic Church over all aspects of life, religious or otherwise; for his championing of ideas of individual responsibility, freedom of conscience and worship; and for showing how powerful, well-entrenched elites can be confronted and vanquished, if only you have the courage’.

Wittenberg is getting itself spruced up to welcome, this coming October, international visitors on the 500th anniversary of the legendary nailing of ‘95 Theses’ to the church door. This might not have happened – printing presses were Luther’s preferred medium.

Visitors won’t get to hear one of Luther’s, two thousand, sometimes ‘sublimely beautiful’, sermons. But they will see Cranach’s vast altarpiece, with Luther, disguised behind a beard, taking the Eucharist at the Last Supper! It’s a metaphor, I suppose. Although, Stanford suggests that Luther was, even in his lifetime, seen as important as one of the apostles. Apparently, Luther’s riposte was that he was nothing but ‘a stinking afterthought’.

During the celebrations, the congregants might hear a service in English or German. That was another of the great achievements of Luther’s life: the translation of the Bible from Latin into the vernacular. This is good as it means people will be able to understand the special prayers, prepared for the occasion, by the Lutheran World Federation and the Pontifical Council for Christian Unity.

One prayer hopes that there will be time ‘to experience the pain over failures and trespasses, guilt and sin in the persons and events that are being remembered’. Are those being remembered people like Martin Luther and Leo X?

Another reads, ‘Thanks be to you for the good transformations and reforms that were set in motion by the Reformation or by struggling with its challenges’. Well, it may not have the beauty or poetry of the language of the King James Bible but you can see the point. The prayer acknowledges Luther’s achievement in starting a movement that, even though it did not intend to, might have saved Roman Catholicism from entropy.

Stanford extols work done by the scholar, Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger, later to be Benedict XVI. As pope, he spoke in 2008 at St. Peter’s, Rome saying ‘Being just simply means being with Christ and in Christ, and this suffices. Further observations are no longer necessary. For this reason, Luther’s phrase “faith alone” is true’. This was an extraordinary, and long overdue, acknowledgement of Luther’s argument. All he ever wanted was debate and discussion but he was vilified and hounded.

In 2010 Benedict visited a sacred place. It was a ‘former Augustinian monastery, at Erfurt’. Luther was a scholar there. The Pope said, ‘We should give thanks to God for all the elements of unity which he has preserved for us and bestows on us anew”. But Luther remains excommunicated. Would he mind?

Stanford wonders what Martin Luther might have thought of the Catholic Church today. He feels that Luther would have admired the way that the Catholics have reformed themselves from within. It has taken generations but finally, Stanford suggests, they have arrived at a solution not unlike Luther’s recommendations 500 years ago. He says that Luther was ‘a man for his own age, but also for every age since, right up to the current day’.

Stanford is an excellent writer able to explain theology and present it as exciting and vibrant. He also finds some jokes.

Works cited

Stanford, P. Martin Luther: Catholic Dissident. London: Hodder and Stoughton. 2017.

A version of this review was first published on pages 34 and 35 in the Weekend section of the Irish Examiner on 15th July 2017. It is reproduced here by permission of the editor.