Dadland by Keggie Carew is subtitled a journey into uncharted territory. But in some ways this memoir is not ‘uncharted territory’ for me as I am almost of an age with its author and my father was born only six months after her father, Tom. And Keggie, an artist, has, like me, lived in County Cork.

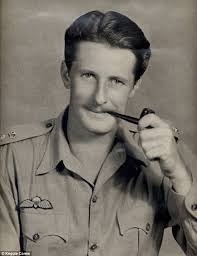

Both our beloved and eccentric fathers are now dead and we are both bruised by grief. All we have are memories and a few photographs. Many of the black and white pictures that litter the text of Dadland could have been in our family’s albums. The two above show Keggie’s parents in the 1940s. The images below are of my parents, Alan and Nancy Smith, during and after the Second World War.

There is also photograph of the cold winter of 1963, showing Keggie’s family, standing by a snowman, that is unbearably recognisable.

My mother’s coat, my mother’s hat, my mother’s ankle boots and my scratchy dufflecoat! It’s almost as if my life appears in these pages. This is the only version of that image that I can find online, showing Keggie and Tom; Keggie’s mother, Jane, has been cropped. And here is one of me in the snow.

It’s almost as if my life appears in these pages. This is the only version of that image that I can find online, showing Keggie and Tom; Keggie’s mother, Jane, has been cropped. And here is one of me in the snow.

But then the territory becomes uncharted since her family experiences are far more extreme than mine. During the Second World War Tom Carew was in the Special Operations Executive F Section and was parachuted into France and then Burma in small self-selected teams to train resistance groups and organise guerrilla warfare. Having been born in 1919 in Dublin, Keggie’s father was known as the “mad Irishman” and also thought to have “the luck of the Irish”.

Tom’s father, Arthur, returned from serving in the Royal Navy in the First World War to an Ireland of Big Houses in which he was employed to look after the horses. Arthur impregnated Maud, a young widow and a lady of the house, and in 1921, after Chute House and Warren House were inflagrated, he left for Cambridge, England with Maud and three children, of whom, only Tom, aged one, was his own. On the day they left, Tom’s half brother remembers, “all the sheep on the farm were slung around the perimeter fence of the house with their throats slit”. Reprisal-torn Ireland was a hostile environment for a man, formerly employed in the British Armed Services and currently in a liaison with a member of the gentry.

Tom’s allegiance was never to his birth country nor to Britain where he grew up but to the Jeds. The Jedburghs were a special unit, originally set up as a collaboration between the British, French and Americans, to be sent to France to cut railway lines, blow up bridges, destroy communications and report on enemy positions as well as other acts of derring-do. Anti-authoritarian as he was, Tom Carew blossomed behind lines, winning the Croix de Guerre and the Distinguished Service Order; of which he was apparently the youngest recipient. And he revelled in the danger and the discomfort.

After France Tom went to Burma and fell in love with the Burmese, later calling them “small, highly independent, thoroughly badly treated, swamped, beautiful people”. He hated the establishment British colonials, regarding them, his daughter thinks in the same way that George Orwell presents them in Burmese Days. The young Irish lieutenant-colonel saw them as “pompous British… trying to cling onto an alien land”.

After France Tom went to Burma and fell in love with the Burmese, later calling them “small, highly independent, thoroughly badly treated, swamped, beautiful people”. He hated the establishment British colonials, regarding them, his daughter thinks in the same way that George Orwell presents them in Burmese Days. The young Irish lieutenant-colonel saw them as “pompous British… trying to cling onto an alien land”.

But after the war Tom Carew was never the same again. He swapped unmitigated success for repeated failure as an employee and as a husband and, even, as a father. Keggie Carew writes with unremitting honesty about the chaotic nature of their family life, economic and emotional impoverishment; their mother eventually institutionalised in a psychiatric hospital in Hampshire. In among the days of avalanches of bills dropping onto the doormat, however, there are memories of wonderful family camping holidays in Spain.

She writes of doomed lobsters in a concrete pool and of surfing being a “heaven-sent pursuit”. Even reading these descriptions I felt a sense of sadness as she says, “Tearing along the shallows, then being dumped on hard wet sand… Yes, this is the time I would go back to, that moment, right then.”

She writes of doomed lobsters in a concrete pool and of surfing being a “heaven-sent pursuit”. Even reading these descriptions I felt a sense of sadness as she says, “Tearing along the shallows, then being dumped on hard wet sand… Yes, this is the time I would go back to, that moment, right then.”

Dadland is not only sad and not only exciting but it is also farcical. Peeing is, Keggie says, “a theme with Dad. When he was living in a Bedford van in London he “drilled a hole through the metal floor into which he slotted a funnel”. After some time the van began to “pong” and Tom discovered that the floor had a double skin. He had been storing his urine in the bowels of his van!

Keggie Carew’s “uncharted territory” in Dadland is her father’s life. He is sinking into the mire of dementia, desperately writing notes to himself:

TOM CAREW’S Brain is collapsing

IS THA

TOM CAREW’S

Brain is ‘switching’

switching away from ‘memory’

memory of people and their names

so you write me off???

not necessarily

I invent – Yes I do – come to my new HUT.

Wednesday 28 July

Tom

and notes to others giving his name but telling them he can’t remember theirs.

Keggie tries to retrieve her father’s life as he forgets it and in this effort she fills a shed with papers dredged up from relatives’ attics and copied from the National Archives at Kew and the Imperial War Museum. It is a huge undertaking requiring research into two separate theatres of the Second World War in both of which her father’s work was clandestine. After the war he was sometimes working undercover. Then there are his three marriages all of which were problematic and caused fissures in family relationships. As Keggie writes, “secrets of these kind get buried deep”.

Keggie tries to retrieve her father’s life as he forgets it and in this effort she fills a shed with papers dredged up from relatives’ attics and copied from the National Archives at Kew and the Imperial War Museum. It is a huge undertaking requiring research into two separate theatres of the Second World War in both of which her father’s work was clandestine. After the war he was sometimes working undercover. Then there are his three marriages all of which were problematic and caused fissures in family relationships. As Keggie writes, “secrets of these kind get buried deep”.

Reflecting the vast amount of material, Dadland is long. The structure is not chronological but like a film with flashbacks. It has been divided into many chapters under section headings such as Dad is a Spy and Mum is a Pakistani, Surprise, Kill and Vanish, and Your Father is a Bastard. The narrative voice changes between academic for the war sections and slangy for the family sections. But the narrative arc is clever – almost like a detective novel – as Keggie follows clues and reveals the answers for herself and her readers.

Keggie saves the best until the end: “Since Dad died he had been in a Barry’s Irish Tea caddy on a shelf in my shed”. The story of what happens to these ashes is one of many hilarious yet moving moments in Dadland. I wish Tom Carew well in his final resting place and, in recommending this book as marvellous, send his daughter an accolade.

Keggie saves the best until the end: “Since Dad died he had been in a Barry’s Irish Tea caddy on a shelf in my shed”. The story of what happens to these ashes is one of many hilarious yet moving moments in Dadland. I wish Tom Carew well in his final resting place and, in recommending this book as marvellous, send his daughter an accolade.

Works cited

Carew, K. Dadland. Chatto and Windus. 2016

Orwell, G. Burmese Days. Harper. 1934.

NB A version of this review was first published in the Irish Examiner (p37 of ‘Weekend’) on 29th October 2016.