Solito Javier Zamora

There are not many good words spoken about people traffickers, and they do not write memoirs. Perhaps they should, since the books would probably sell well as the reading public tackled the narratives in the hope of understanding: firstly how it feels to be such a person and secondly, how they can be stopped. Ireland has its own culture of immigration ranging from the recent film, Aisha, the novel, A Slanting of the Sun, by Donal Ryan and the exhibition at the Triskel Centre depicting Direct Provision Centres in photographs of derelict rooms with damp walls and filthy mattresses.

Here, in Solito, the story is told by Javier Zamora, who as a child migrated from El Salvador to California, a trip which was arranged by Don Dago. Explaining why his prices are high, and non-negotiable, Don Dago describes himself, in a line delivered without irony as ‘only one pearl in a long pearl necklace’. He takes his cut and the remainder of the cash is passed, in backpacks, down the line as strangers bundle the child from one to another.

Zamora’s parents have already left their country: his father for political reasons and, later, his mother for economic ones. He, their child, is ensconced with grandparents and aunts in the fishing town of La Herradura, down a dead-end road. As he grows from 5 years old to 9, Javier hears the mantra about how ‘La USA is safer and richer’. Every week he speaks to his mother on the phone, and the conversation centres only on his trip to join her.

Don Dago journeys with him for only a short time and then Zamora is told to stick close to a man named Marcelo who comes from his own locale. In return for his nervous smiles the child receives, from his neighbour, only glowering silence. Instead, he snuggles up to Carla, and her mother Patricia, and the three stick together in their sub-group of six which also includes Chino, Chele and the forbidding Marcelo.

Zamora likens the group of terrified and desperate humans to some ants that he once saw in a flood. The creatures linked their legs and antenna to form a living raft and floated on the top of the water. Can the six compadres reach the promised land or will they, like the insects, sink to the bottom still holding on to each other for dear life? Zamora’s account is, of course, heart-breaking and heart-warming.

Just as it is rare to find an account of illegal crossings produced by traffickers, it is unusual to find one by border guards. And yet most people, if they are honest, are much more sympathetic to those who prevent entry than to the immigrants themselves. It is easy to sympathise with Zamora’s plight as a vulnerable minor, powerless to negate the wishes of adults. But those feelings do not necessarily transfer to a welcome for arrivals in a country, like this one, with a serious shortage of housing.

In her novel, Spring, Ali Smith studies the daily routine of an officer in a detention centre, and her mindset. There is cognitive dissonance between her concept of herself as a person and the mundane cruelty of her behaviour. These are the areas which need exploring, perhaps, rather than wallowing in empathy for a child, now an adult, who left a country we know little of, to travel to another country far from ours. The moral choices that must be made in Ireland concern what is happening here and now in front of our eyes.

Works cited

Smith, A. Spring. Penguin. 2021.

Zamora, J. Solito. One World. 2022

A version of this review was first published on page 44 of the Weekend section of the Irish Examiner on 17th December 2022. It is reproduced here by permission of the Editor.

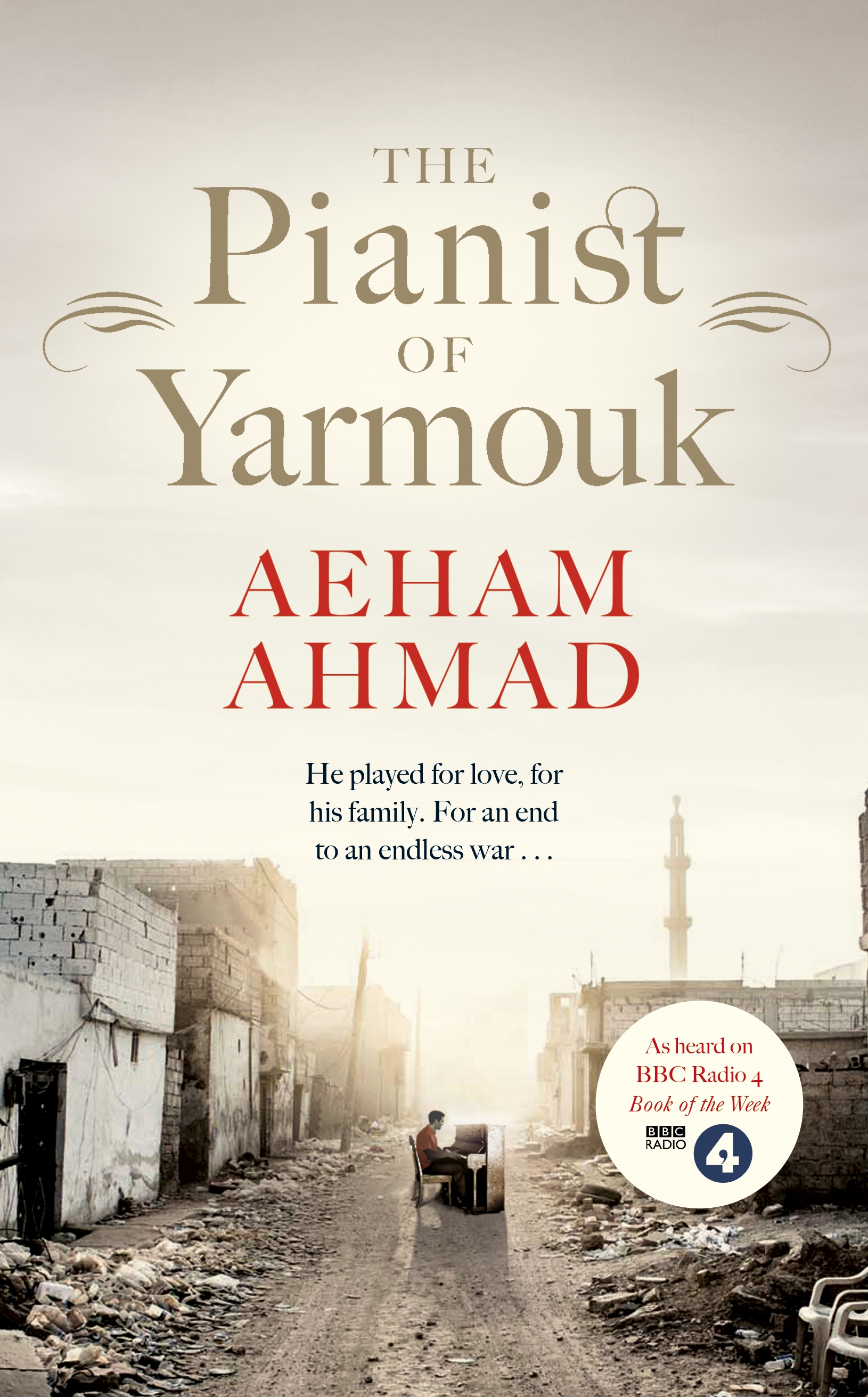

From every conflict emerges an iconic photograph. Nine-year-old Kim Phuk, in 1972, running naked from a napalm attack during the Vietnam War, or the body of refugee Alan Kurdi, aged three, washed up on the shore near Bodrum in 2015. The 2014 image of Aeham Ahmad, playing an upright piano surrounded by the debris of Yarmuck, is also unforgettable.

From every conflict emerges an iconic photograph. Nine-year-old Kim Phuk, in 1972, running naked from a napalm attack during the Vietnam War, or the body of refugee Alan Kurdi, aged three, washed up on the shore near Bodrum in 2015. The 2014 image of Aeham Ahmad, playing an upright piano surrounded by the debris of Yarmuck, is also unforgettable.