But such a form as Grecian goldsmiths make

Of hammered gold and gold enamelling

To keep a drowsy emperor awake;

Or set upon a golden bough to sing

To lords and ladies of Byzantium

Of what is past, or passing, or to come.

English readers of This Orient Isle by Jerry Brotton would think of Shakespeare’s lines ‘this sceptred isle … this precious stone set in the silver sea’ from Richard II, but the Irish would probably remember Yeats’s poem Sailing to Byzantium. Like the final stanza of that poem, the pages of the book are filled with references to oriental gold. Ironically, for lovers of Yeats’s poem, Brotton tells of a gift, from Queen Elizabeth I to Sultan Murad III, not the other way around, of a clockwork organ which was played, in 1599, to entertain ‘the lords and ladies of Byzantium’ in the same palace that Yeats chose for his golden mechanical bird. The Sultan was not ‘drowsy’ but delighted, and offered the organ-maker, Thomas Dallam, his choice of the palace concubines. It seems that Dallam merely accepted a bag of gold.

This Orient Isle explains Elizabeth’s alliances with the Ottoman and Persian Empires as well as the Moroccan Sultanate, relationships which frequently distracted her from her ‘disastrous military campaign to try to crush Catholic rebellion in Ireland’.

Although Brotton does not dwell on it, the narrative suggests many parallels to Europe’s current relations with the Islamic world. As Edward Said points out in his theory of Orientalism, Judo-Christian Europeans often see Muslims as the ‘Other’, as something alien and dangerous. Said argues that because of misunderstanding or ignorance, we cast all Muslims as the enemy in the ‘war on terror’.

Brotton sets out to detail and analyse, the process by which Protestant England, with her queen who was to be excommunicated in 1570, was seeking an alliance with this ‘Other’. England was struggling against against Catholic Spain, France and the Holy Roman Empire who had a stranglehold on trade. In 1566, the Bishop of Winchester wrote ‘the Pope is a more perilous enemy unto Christ, than the Turk: and Popery more idolatrous than Turkery’.

The English merchants and explorers, like many current Europeans, did not have much of an understanding of Islam; one of them, Anthony Jenkinson explained, in 1558, the difference between Sunni and Shi’a in terms of their facial hair: ‘the Persians will not cut the hair of their upper lips, as the Bukharians and all other Tartars do’. The task of these emissaries, after all, was not theological but mercantile. In pursuit of trade Jenkinson tackled the frozen wastes of the North West Passage and arrived in Persia after a long and hazardous trek via Moscow. He found that the heavy cloth that he offered for sale was of more interest in the cold climes of Russia than in the warmth of Persia where he saw ‘golden and silken garments’.

Another traveller was Henry Roberts, the first English Ambassador to Morocco (1585). Roberts, who had been a soldier, was settled in Ireland after a period of quashing insurrection. Not only was he reluctant to ‘yield his place’ in Ireland, but he had no experience of trade or diplomacy. Brotton writes that to ‘a soldier like Roberts, used to the monoglot world of England and Ireland and its stark religious divisions between Protestantism and Catholicism, the multi-confessional and polyglot world of Marrakesh must have come as a massive shock’. In the three years that he was there, however, Roberts seems to have spent more time engaged in military and political matters than commerce. He traded munitions and agitated for the Moroccan emperor, al-Mansur, to join an anti-Spanish league.

Roberts was working under the auspices of the Earl of Leicester, as was a later adventurer, Anthony Sherley. After Leicester’s death Sherley’s patron was the ‘equally intemperate’ Robert Devereux, 2nd Earl of Essex, who would, the following year, be attempting to subdue O’Neill in Ireland.

Sherley is described as ‘a born intriguer, a complete opportunist’ and ‘ a completely sinister person’. Nevertheless, shortly after his arrival in Persia in 1598, Sherley’s relationship with Shah Abbas was, states Brotton closer than ‘that of any other Elizabethan Englishman and Muslim ruler’. Extraordinarily, by 1599, Sherley was able to claim ‘the right to represent the shah’s interests in Europe and to act like a Persian Mizra (prince) with the authority to mingle with kings and emperors’. Now he ‘was proposing to broker a grand anti-Ottoman alliance between Persia and Europe’s Catholic rulers’. It is not surprising that he was never able to return to England.

It is surprising that in 1888 a pamphlet written by the Reverend Scott Surtees suggested that Sherley was, in fact, the author of Shakespeare’s plays. Surtees argued that Sherley knew the ‘habits and the ways, the customs, dresses, manners, laws of almost every known nation’ and obsessed that the name Antonio, used in so many plays, came from Sherley’s own forename, Anthony.

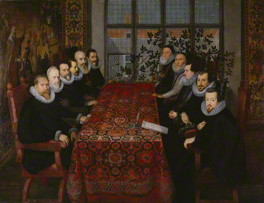

Whether or not Sherley was ‘he who wrote these plays’, Brotton, himself, is extremely interested in Shakespeare’s works and has searched through them, like a monkey looking for fleas. In his first paragraph, Brotton, writes of Abd al-Wahid bin Masoud bin Muhammad al-Annuri as ‘a tall, dark, bearded man’ who in ‘is instantly distinguished from the crowd by his long black robe (thawb), bright white linen turban and the huge richly decorated steel scimitar, a Maghreb nimcha, which hangs from his waist’.

Later in the introduction, Brotton, states that ‘it is possible to discern some of the local raw material on which Shakespeare might have drawn for his portrayal of the noble Moor.’ The Morrocan envoy was in London in 1600-1601, the latter being the year that Shakespeare started writing Othello. But Brotton’s rather pedestrian recounting of the story of Othello in the chapter ‘More than a Moor’, along with his foregrounding of every possible reference to the Orient (such as the word ‘surely’ in Twelfth Night being an obvious pun on the name Sherley) are much less convincing and exciting than his account of Elizabethan deeds of derring-do.

Works Cited

Brotton, Jerry. This Orient Isle. London: Random House. 2016. Print.

Said, Edward. Orientalism. New York: Pantheon Books. 1978. Print.

Yeats,William Butler. “The Wild Swans at Coole”. The Wild Swans at Coole. Dublin: Cuala Press 1917. Print.

NB This review was first published in “Weekend” (p5) in the Irish Examiner on 28th May 2016