How is it possible that I have never heard of this wonderful writer? I came to this novel, unenthusiastically, having just completed Sebastian Barry’s superb Days Without End . I have long been a fan of Barry’s work and have read almost everything that he has written. On the back cover of Barry’s 2005 novel A Long Long Way Frank McGuinness says that Barry ‘writes like an angel’ and I agree with that. McGuinness adds that Barry is ‘on the side of the angels that fell’.

. I have long been a fan of Barry’s work and have read almost everything that he has written. On the back cover of Barry’s 2005 novel A Long Long Way Frank McGuinness says that Barry ‘writes like an angel’ and I agree with that. McGuinness adds that Barry is ‘on the side of the angels that fell’.

But I have now discovered that Aslam is Barry’s equal: he too ‘writes like an angel’ and ‘is on the side of the angels that fell’.  I will be putting his four previous novels on my birthday list. If you look at the video below of the choir at King’s College Chapel in Cambridge you will see, between one minute 14 seconds and two minutes 12 seconds, a sort of representation of the regiments of ‘angels’ who fell in the First World War, and are currently falling all over the world, in its various theatres of war, as well as in so-called peaceful democracies.

I will be putting his four previous novels on my birthday list. If you look at the video below of the choir at King’s College Chapel in Cambridge you will see, between one minute 14 seconds and two minutes 12 seconds, a sort of representation of the regiments of ‘angels’ who fell in the First World War, and are currently falling all over the world, in its various theatres of war, as well as in so-called peaceful democracies.

The Golden Legend, deals directly with angels. Or, at least, the angel Gabriel. Gabriel ‘from heaven came’ and visited Mary, mother of the Christian God, to impregnate her; he visited the Prophet Mohammed to dictate words of the Koran. An equivalence, the liberal thinkers among us – leave Trump out of this – might think. But, now, to The Golden Legend.

For Pakistan born, Aslam, who was brought up and educated in the north of England, paper is the “strongest material in the world. Things under which a mountain will crumble, you can place on paper and it will hold: beauty at its most intense; love at its fiercest; the greatest grief; the greatest rage”.

Paper is literally at the centre of the novel, which opens in the home of Nargis and Massud, architects who live and work in a defunct paper factory now converted into their home/work space. Surrounding this edifice is the city of Zamana, an Urdu word meaning period, era or age, pulsating with the noises of modern and ancient Pakistan. One sound is that of the loudspeakers, in the multiplicity of mosques, which, as well as emitting the muezzin, are being violated by a mysterious broadcaster who, night-by-night reveals the scurrilous secrets of citizens. Vigilantes punish the accused, especially Christians, especially women.

The former factory, however, is set in an oasis of bright fertility: an orchard, largely developed for cheap housing, but leaving a demesne of trees; almond, rosewood, mango, silk-cotton and coral. From the beginning the novel seems surreal, juxtaposing calm with sudden violence, silence with cacophony, cleanliness with filth.

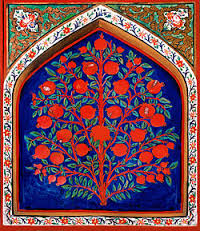

Nargis and Massud’s vast library contains two elaborate and ornate Wendy House-sized miniature mosques, both reproductions of cathedrals/mosques which served in different ages, as places of worship for both Christians and Muslims. Nargis and Massed use them in the winter months as small studies; easily heated in the freezing space. In the summer they are winched up, towards the high ceiling, hanging, floorless, above the dwellers. Elsewhere in the house, huge, spread, swan wings are pinned to the pink wall alongside the wings of a golden eagle, a parakeet and other birds. The house is full of ‘intense’ beauty and provides a crucible from which the architects can create more beauty in an ideological attempt to fight, as Aslam himself does with his art, the evil of the outside world.

It is not magic-realism: it is Aslam’s portrait of a world in which all that exists is extreme. Social and religious hierarchies are fiercely maintained, with the Christians, including two other central characters, Helen and Lily, as the butt of prejudice; their blood thought to be black, not red. Nargis thinks “everything this land and others like it were going through was about power and influence. All of it. And these struggles of Pakistanis were not just about Pakistan, they were about the survival of the entire human race. They were about the whole planet”.

Life is precarious amid frequent acts of sectarian violence. Vicious assaults against vulnerable flesh come from the most unexpected sources and are perpetrated against gentle and educated characters as often as not. There is no sense that those who might be considered liberal, rational and moral are thought of as such by their neighbours.

Strangely, the most shocking knife slashes are directed at a book from the Islamic section of one of the city’s oldest libraries. This book is ‘That They Might Know Each Other, words inspired by a verse in the Koran. A meditation of how pilgrimage, wars, trades and curiosity had led to contact between cultures’. This book, written by Massud’s father, contains reproductions of iconic art.

The first page to be vandalised contains an image of the Prophet Mohammed receiving a revelation from the angel Gabriel. ‘He perforated the face with the steel tip, and then the blade continued upwards through the angel’s headdress, the various ribbons and gems. Continuing, it cut into the sky full of gold stars’. The congress between Christianity and Islam is severed in an act of ‘conscienceless temper’.

Later, and, seemingly whilst Nargis is lying, sleepless, in bed, the entire book is ‘razored’ into pieces.

In an act of indefatigable hope and unremitting courage Nargis begins the task of sewing, her needle threaded with shining gold, the 987 pages back together. She is performing her own version of the Japanese process of Kintsugi. “The art of mending pottery with lacquer mixed with powdered gold. The logic was that damage and restoration were part of the story of an object, to be accepted rather than concealed. Some things were more beautiful and valuable for having been broken’.

In The Golden Legend, Aslam opposes the vituperative Pakistani laws of blasphemy with his call for the freedom of language, both written and spoken, especially when uttering words of love. He, like Nargis, is trying to accept and restore damage. He states that when he starts writing a novel, “I begin to think … beyond the despair, what is the moment of hope?”

Works cited

Aslam, N. The Golden Legend. Faber & Faber. 2017.

Barry, S. A Long Long Way. Faber & Faber. 2005.

—. Days Without End. 2016.

An earlier version of this review appeared in The Irish Examiner‘s Weekend Section page 37 on 8th April 2017.

See also is a short piece by Aslam which describes his working practices.

It was introspective, dreaming of ‘a land whose countryside would be bright with cosy homesteads, whose fields and villages would be joyous with the sounds of industry, with the romping of sturdy children, the contest of athletic youth and the laughter of happy maiden’. It sounds suspiciously like Hitler’s Aryan ideal, which is still encapsulated in

It was introspective, dreaming of ‘a land whose countryside would be bright with cosy homesteads, whose fields and villages would be joyous with the sounds of industry, with the romping of sturdy children, the contest of athletic youth and the laughter of happy maiden’. It sounds suspiciously like Hitler’s Aryan ideal, which is still encapsulated in