dannymorrison.com

35 years ago, on the 30th October 1981, the H-Block hunger strike officially ended. In Long Kesh prison, a sequence of ten deaths had taken place between May and August. In 2005, Richard O’Rawe, who served as the IRA public relations officer inside the jail, wrote Blanketmen, in which he asks whether the final six hunger strikers were forsaken by comrades on the outside.

Blanketmen, first published in 2005, has been reprinted in 2016 with a new foreword by Richard English. Setting the context for the strike and trying to unpick the claims and counter-claims, English demands that we engage with Blanketmen if we want “to understand those grim years of prison war”. Indeed, he insists that the book is not only “a compelling and personal narrative” but contains “wider insights into republican activism and legacies”.

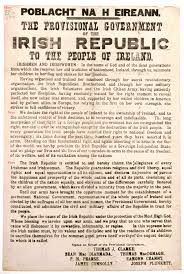

2016 is a telling year for Blanketmen to be re-presented, because, as O’Rawe states “there was an almost biblical reverence for the 1916 Proclamation” among ‘Special Category’ prisoners. As we revisit and rethink the complexities of the Easter Rising, it seems appropriate to reconsider the controversial events of the summer of 1981 when certificates were written for ten deaths from ‘self-imposed starvation’ in Long Kesh.

O’Rawe, receiving a death threat in 1991, kept silent for many years but as the century turned, and the armed struggle gave way to the Peace Process, he decided that it was his duty to expose “duplicity”. O’Rawe attempts to peel “away the layers of carefully scripted myths that have surrounded this momentous event in Irish history, the most insidious being that the prisoners were always in complete control of the hunger strike”.

O’Rawe’s prologue begins in early July 1981 when “the leadership of the republican prisoners in the H-Blocks accepted a set of proposals that had been presented to them by the ‘Mountain Climber’, an intermediary from the British Government”. But the Army Council of the IRA rejected the offer and six more men died, the last one on 20th August. The strike ended, partly due to the strikers’ families intervening, on 30th October and, soon after, most of the rights demanded were granted.

Since 1976 some Republican prisoners, furious at being classed as criminals rather than politicals, refused to conform to prison rules, wearing blankets instead of “monkey suits”. When O’Rawe arrived that year at Long Kesh the “streaker” tradition was well established and with each day that passed Blanketman O’Rawe lost a day’s remission.

Since 1976 some Republican prisoners, furious at being classed as criminals rather than politicals, refused to conform to prison rules, wearing blankets instead of “monkey suits”. When O’Rawe arrived that year at Long Kesh the “streaker” tradition was well established and with each day that passed Blanketman O’Rawe lost a day’s remission.

Frustrated by stasis, O’Rawe and his comrades, including Officer Commanding, Brendan Hughes or ‘The Dark”, and public-relations officer, Brendan ‘Bik’ McFarlane, instituted a ‘no wash’ protest. Although the prisoners felt that they were “being buried alive in a sewer” they refused to comply with regulations.

Prison guards subjected the political prisoners to beatings and torture and many of the latter submitted to the Long Kesh regime leaving only a core of “hard men” resisting. These, in order to reinforce their position, and with permission from the Army Council, reluctantly decided to embark on a hunger strike. Strikers were selected from a list of IRA and INLA volunteers.

O’Rawe’s account of the organisation of the hunger strikes displays an unsurprising disconnect between the Army Council on the outside and the inmate leaders. Communication was difficult; additionally vehement disagreements and strict enforcement of “need to know” contributed to the chaos.

Meanwhile men died, their skin “breaking out in sores”. For what? Five rights: not to have to wear prison uniform, not to do prison work, to have free association amongst themselves, to receive weekly parcels/visits and unlimited letters and to have their remission returned. Apparently the ‘Mountain Climber’ offered: their own clothes, parcels/visits and letters, unofficial segregation, regular free association and acceptable ‘work’.

O’Rawe claims that he and ‘Bik’, as the senior IRA officers inside the jail, and the only two who ‘needed to know’, accepted these terms, although ‘Bik’ McFarlane has always refuted this. The Official IRA line is that Gerry Adams and his colleagues had been awaiting a second, better, but undelivered, offer from the ‘Mountain Climber’. O’Rawe wonders if the Army Council’s refusal to end the strike was a political move to ensure the election, on 20th August, of Owen Carron, standing as the Anti H-Block/Proxy Political Prisoner, to replace the deceased Bobby Sands as MP for Fermanagh/South Tyrone.

Blanketmen is a brave book written by a man who is passionate not just about his “ten dead comrades, who gave their lives for the Republic” but one who cherishes republicanism. He also spins a good yarn. His reportage of the banter between prisoners is priceless. As Richard English commands in his foreword, engage with Blanketmen; I add that you will also find it engaging.

Works cited

O’Rawe, Richard. Blanketmen: An Untold Story of the H-Block Hunger Strike 2nd ed. Dublin: New Island. 2016. Print.

Wolfe Tones. “Longkesh” Let the People Sing. Dublin: Dolphin Records. 1972. LP.

NB A version of this review was first published in the weekend section (p37) of the Irish Examiner on 22nd October 2016.