The Untameable Guillermo Arriaga

Guillermo Arriaga is a prize-winning novelist, screenwriter and filmmaker. Arriaga’s signature style is to tell parallel stories. In The Untameable his task seems particularly unwieldy in that short extracts from the life of Amaruq, an Inuit wolf-hunter, must interact with a story of vengeance located in the barrios of Mexico City. A clue comes early, in an aside about a neighbourhood dog, ‘a cross between an Alaskan Malamute and a Canadian wolf’. This beast, named ‘Colmillo’ translatable as ‘Fang’ references Jack London’s 1906 novel about a wolfdog, White Fang.

In the darkness of the south poor caged Colmillo howls to invisible peers but in the north of the continent, on snowy plains free from constraint, Nujuaqtutuq, translated as ‘Untameable’, silently leads his pack across a frozen river. In spite of his literary credentials Arriaga identifies as ‘a hunter who writes’. In this novel he uses the wild animals, the hostile terrain and the seemingly hopeless mission undertaken by Amaruq as metaphors for the less romantic struggles of young Juan Guillermo who is trying to lift himself from the mire of the slums.

Amaruq tracks wolves and sells their pelts as his livelihood, although owing to his initiation by, and relationship with, his grandfather, it is also his vocation. Man and wolf are equal in the contest. If Amaruq continues with his quest he will surely die: only two bullets remain, he has very little food and his windproof clothing is torn. The wolf pack sleeps, encircling his tent like wagons forming a malevolent laager. Nujuaqtutuq, his foe, wears the crown, having won it from the previous holder, Tulugak, who was left in a gully bleeding out. Now the new king must prove himself and find food for his subjects or they will perish and his genes will be lost.

It is different in the alleyways and rooftops of the city. Corruption infiltrates every layer of society, even the primary classrooms. Nothing is natural. Children become foot soldiers and fight and die, their pre-pubescent bodies maimed and their minds warped before matriculation.

Juan Guillermo lost his twin, Juan José in utero and is now living for two. The surviving child seems to have the characteristics of an oppositional pair within his psyche. He is intelligent and prepared to study. At the same time he is obsessed with girls and women, getting expelled from elementary school, for heavy petting. He is involved in criminal activities and an enemy of the police commandant, Zurita. But he is also an aesthete, drawn to the local Christian society, the ‘Good Boys’, a group of self-flagellating, Bible-spouting teenagers.

Arriaga intersperses his double narrative with mini-treatises from philosophy, anthropology and religion. Many of these focus on ideas or legends, from around the world and from history, about death and the concept of the soul. They are presented as Juan Guillermo’s perusings since his tale is told in the first person. Amaruq’s third person story might be seen as a wolf fable as the quest is passed between grandparent, uncle and nephew. Readers of The Untameable can learn from the contest between man and wolf but Juan Guillermo must take his lessons from the travails of life in the favelas.

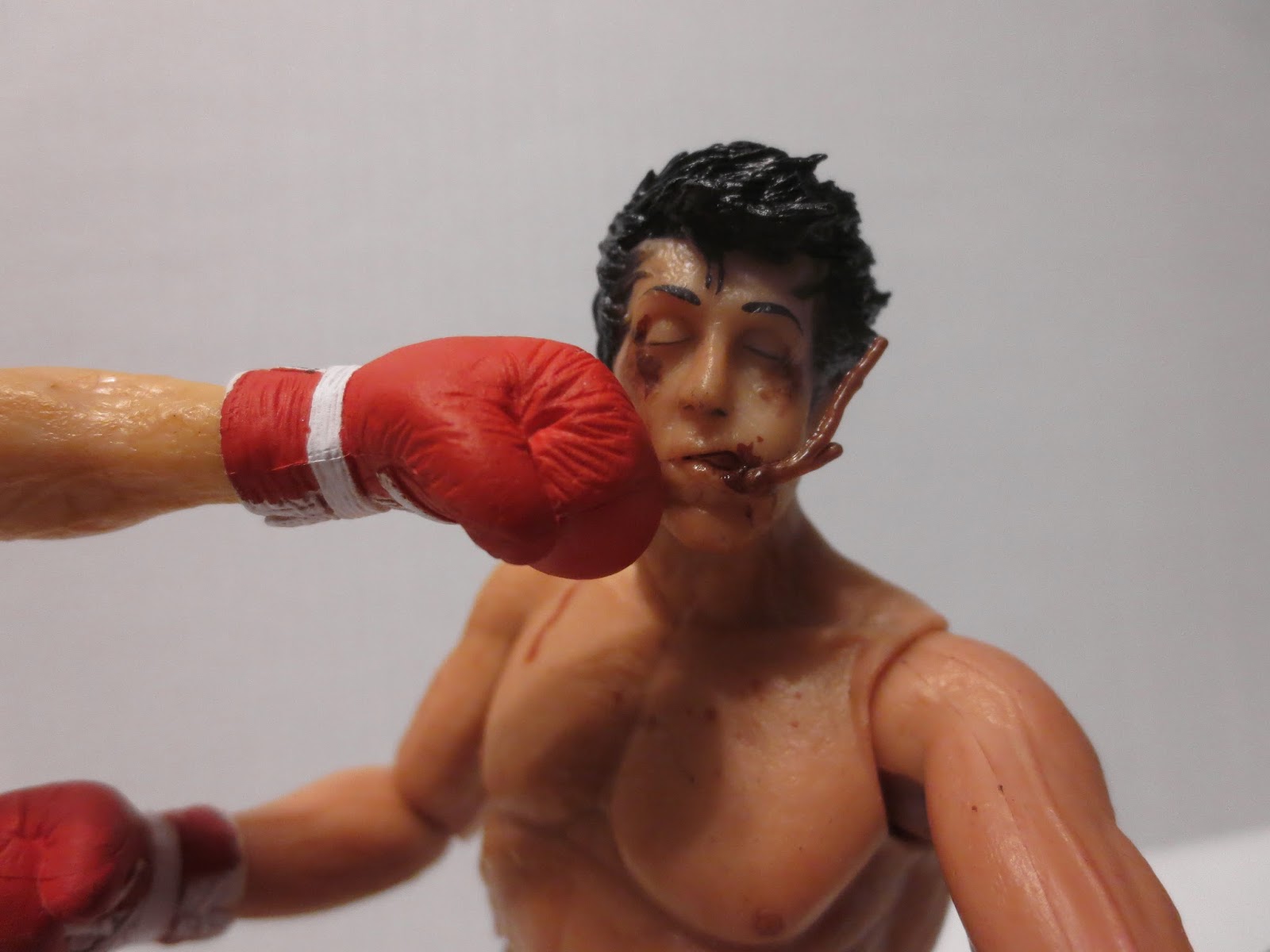

The Untameable is macho: female characters are stereotypical, one-dimensional and likely to be raped. Men are physically strong and often violent with a propensity to murder. It is a fast-moving, intriguing and virile novel: Jack London would have recognised a call from the wild.

Works cited

Arriaga, G. The Untameable. Translated by Frank Wynne and Jessie Mendez Sayer. MacLehose. 2021. First published as El Salvaje by Editorial Alfuguara. 2016.

London, J. White Fang. Macmillan. 1906.

A version of this review was first published on page 34 in the Weekend section of the Irish Examiner on 22nd May 2021. It is reproduced here by permission of the Editor.

From every conflict emerges an iconic photograph. Nine-year-old Kim Phuk, in 1972, running naked from a napalm attack during the Vietnam War, or the body of refugee Alan Kurdi, aged three, washed up on the shore near Bodrum in 2015. The 2014 image of Aeham Ahmad, playing an upright piano surrounded by the debris of Yarmuck, is also unforgettable.

From every conflict emerges an iconic photograph. Nine-year-old Kim Phuk, in 1972, running naked from a napalm attack during the Vietnam War, or the body of refugee Alan Kurdi, aged three, washed up on the shore near Bodrum in 2015. The 2014 image of Aeham Ahmad, playing an upright piano surrounded by the debris of Yarmuck, is also unforgettable.

Whilst slaving in a bookstore he teaches himself to read, starting with The Golden Age of Spanish Poetry. By the time the action begins he has read ‘Virgil and Dante, Catullus and Bécquer, Boccaccio and Balzac, Homer and Tolstoy, Cervantes and Dickens, Austen and Borges, Pylorus and Aesop. His idiolect ranges from high culture to the lowest but lacks the normal register that most of us use to communicate.

Whilst slaving in a bookstore he teaches himself to read, starting with The Golden Age of Spanish Poetry. By the time the action begins he has read ‘Virgil and Dante, Catullus and Bécquer, Boccaccio and Balzac, Homer and Tolstoy, Cervantes and Dickens, Austen and Borges, Pylorus and Aesop. His idiolect ranges from high culture to the lowest but lacks the normal register that most of us use to communicate.