Ibram X. Kendi and Keisha N. Blain: Editors

Impressive. Ibram X. Kendi and Keisha N. Blain have produced a history of Black America which circumvents the prevailing white accounts. They are not, obviously, the first to undertake such a task but they are the only ones who have gathered 80 contributors. Each writer has five years to address. Each of the 10 decades has 8 pieces and a poem as a coda. And thus Four Hundred Souls celebrates the 400th anniversary of the two dozen Ndongo people, kidnapped from what is now Angola, who disembarked from the White Lion at Jamestown, Virginia in 1619. That was before the Mayflower docked in 1620, an arrival for which a national holiday is designated.

Kendi is founding director of the Boston University Centre for Antiracist Research and has been named, by Time magazine, as one of the world’s 100 most influential people. From his work, and undoubtedly from his own life experience, Kendi knows what it is to be oppressed. He and co-editor, historian Keisha Blain, have taken pains to celebrate diversity in their invitations to people: those ‘who identify (or are identified) as women and men, cisgender and transgender, younger and older, straight and queer, dark-skinned and light-skinned’. They are all Black.

Every piece is relatively equal in length and in this way the ‘historians, journalists, activists, philosophers, novelists, political analysts, lawyers, anthropologists, curators, theologians, sociologists, essayists, economists, educators, poets and cultural critics’ make up a ‘choir’. It all sounds quite romantic and yet it works: everyone must focus, in a few words, on half a decade of their history, whilst voicing personal ideas.

Kendi mentions, in his introduction, the old spiritual: ‘We shall overcome”. The book, Four Hundred Souls, provides the lyrics for a new epic song, written in 2019, a spiritual which documents a ‘soulful history’. Kendi practises what he preaches in that his short essay is melodic and poetic as he extends a metaphor about the pregnancy, gestation, delivery date and birth of African America.

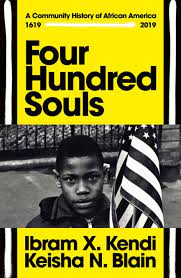

Even from a cursory glance Four Hundred Souls is weighty. Book designer, Barbara M Bachman, uses the colour black to dominate the exterior and interior of the book, deploying striking reverse or WOB (white lettering on a black background). It seems that everything has been done to project the idea of Blackness in this recreation of Black American history conceived by a talented congregation of living Black American people.

Clearly, owing to its characteristics, Four Hundred Souls itself is more likely to become an historical artefact rather than a reliable chronicle. It is a snapshot of how Black people in 2019, when all the essays were written, responded to a specific five-year long moment of time. Looking far back to the seventeenth century or only a short way to 2014 onwards, the writers ricocheted off events in their own ways. It is hard to stick to facts anyway: in those earlier days records were kept only by white people, but in Four Hundred Souls historical gaps can be filled in with imagined events.

Writing of 1644-1649 novelist Maurice Carlos Ruffin tells, in the first person, a fable of Anthony Johnson and the ‘wife of his skin’ Mary. Johnson, a freed slave, is now a landowner and employer meeting with a white freebooter who tries to best him in the matter of a calf. This is a fascinating short story which, like all of its genre, leaves as much untold as expounded. Maybe it must be thus in the narration of the early years of Black America. Bills of sale survive but there is no Black-scribed Shakespearean play or Decameron.

In 1909 W.E.B. Du Bois, a Black sociologist known for founding the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) defined the role of the ‘Negro folk-song’, as ‘the rhythmic cry of the slave’. In 2019, 110 years later, Corey D. B. Walker writes of ‘the sacred sound of freedom’ in an article entitled ‘The Spirituals’.

For Walker the 18th century was ‘a conjuring space’ for polyphony and syncopation. He waxes lyrical about the range and complexity of the musical forms within enslaved communities. These works cannot be translated effectively into the ‘idioms of European notes and categories’. Walker asks a big question: ‘what is the sound of Black freedom’? Rather than answering it himself he returns to the words of W.E.B. Du Bois, who with his trademark rhetoric pursues the query: ‘Do the sorrow songs sing true?’

Music, like the poems that designate the skeleton of the structure of Four Hundred Souls, punctuates and underlies many of the topics chosen for erudition. For memoirist Kiese Laymon, writing of the 19th century, there is another trope. His outpourings centre on cotton. Specifically he describes an old bulb of cotton that he saw as a child with its ‘nearly crumbling brown flower holding the actual cloud’. The answer to every question about a picker’s life, such as why their hands are rough and fingers swollen is that same one word ‘cotton’. Even more personal matters, such as not talking much, are down to ‘cotton’.

Laymon’s response to the inheritance from his forebears runs to four syllables: ‘I blame cotton’. Nevertheless he became the man who still finds himself sleeping with ‘a bulb of cotton on the dresser by the bed’. He believes that that the once white boll represents ‘Black bodies, Black deaths, Black imaginations, Black families’.

Moving forward to the 20th century accounts of legislation proliferate demonstrating the ways in which some Black people attempted to achieve equality. Some of these addressed the segregation of education. In 1954 the Supreme Court, led by Chief Justice Earl Warren, ruled that ‘separate educational facilities are inherently unequal’. Sherrilyn Ifill’s chapter is called ‘The Road to Brown V. Board of Education’. Ifill is the current president and director-counsel of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund and is no lightweight. She has been woman of the year and attorney of the year and is currently basking in the title of Spirit of Excellence. This would be the realisation of dreams of her forebears.

In her conclusion Blain wants to talk about the saying ‘Our Ancestors’ Wildest Dreams’. She feels somewhat bereft in that there is no precision to her knowledge of her own great-great-great-grandparents. She knows that they were enslaved in the Caribbean but not where. She has no texts, such as letters or journals in which to read of their desires. Just as Maurice Carlos Ruffin had to create the tale of Anthony Johnson so Blain ‘is left to imagine and question’.

To this end Blain presents her own dream, thinking that it might reflect those earlier ones like a mirror. What she fantasises about is a world in which ‘Black people, regardless of gender, religion, sexuality, and class, are living their lives uninhibited by the chains of racism and white supremacy that bind us still’. Blain does not consider that this situation is a reality or that it will be soon.

No one could disagree with Blain, as evidenced by 21st century phenomena such as #Black Lives Matter, here explained by Alicia Garza, its co-creator. Additionally, states Blain, the world is witnessing ‘the disproportionate impact of COVID-19 diagnoses and deaths’ on Black people. She mentions a number of other indicators: maternal mortality rates, educational achievement, police violence and incarceration statistics alongside other shameful matters. At the same time she optimistically counsels the charting of a ‘path’ to a time when, indeed, Black people will overcome.

Works cited

Kendi, I.X. and Blain, K.N. Eds. Four Hundred Souls: A Community History of African America 1619-2019. The Bodley Head. 2021.

A version of this review was first published on pages 33 and 34 of the Weekend section of the Irish Examiner on May 15th 2021. It is reproduced here by permission of the Editor.